Story by Fletcher Cleaves

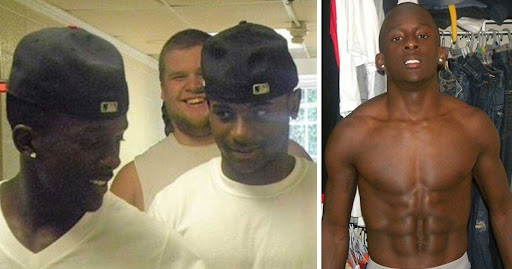

In a flash of blue light, my life was changed forever. It was a beautiful evening after a rainy day in September, and almost kickoff time for the first NFL game of 2009. My roommate Dayne and I were driving back from Buffalo Wild Wings to our dorm to watch the game. I could smell those wings in the back seat waiting for us. We were talking about what first-year college guys talk about—girls, sports, and whether the Titans or the Steelers were going to win. We were football scholarship students at Lambuth University, excitedly gearing up for our first college game.

As I was driving, I checked my rearview mirror when Dayne suddenly yelled, “Fletch, watch out!” I realized that the oncoming car was crossing the double yellow line, coming straight at us. In that moment, I saw the woman who was driving that car. She was looking down, and the blue light of a device lit her face in the growing darkness around us. I panicked. The 1988 Samurai I had driven in high school did not have power steering, so I had to use some muscle to turn it. But this 1999 Honda Accord had power steering. In my desperation, I didn’t have time to think about power steering. I overcorrected and jerked the wheel too hard.

I know she must have been able to see in her rearview mirror the result of her decision to look down at her screen instead of at the road, but she never stopped to see if we were okay. Her car raced away out of sight, but my car was already spinning out of control. I heard a deafening BOOM! as we hit a guardrail and then the car was airborne. We seemed to be floating weightless over a bridge and toward a steep embankment. It was surreal. Each second stretched out like ripples widening in a pool. I could tell that I was upside down. I remember thinking, ‘Man, we are in the air for a long time!’ I braced for impact.

After months of intense training for my first year of college football, I felt my body tensing for the toughest tackle of my life. It was like running a ball across the middle of the field when you know you’re going to get hit, but you don’t know exactly when. I kept expecting it, and I knew it would be bad. Yet even though it couldn’t have taken more than a few seconds for us to crash at the bottom of that deep ditch, it was like watching an eerie slow-motion playback moment from a big game. I remember pulling my head down toward my shoulders in anticipation. But I don’t remember the crash itself. I was knocked unconscious immediately.

I don’t know how long I was out, but when I came around, I noticed that the roof of the car had caved in. The next thing I heard was Dayne’s voice yelling, “Fletch! Fletch!” which immediately woke me up. In my mind, I thought he was trying to wake me up in our dorm room and I was just asleep. But it was so dark, and all around us was a misty fog. My first thought was, ‘My dad’s going to kill me. I just got this car!’ It was my high school graduation gift in June from my parents. I tried to roll over, but I couldn’t move. I was pinned under the roof of the car, lying on my right arm.

Then I tasted mud and leaves, and I began to realize I was in a serious situation. Dayne was trying to get me out of the car, but he was so badly injured and bleeding that he couldn’t do it. Why wasn’t I feeling any pain? Why couldn’t I move? Then I had a thought that made my blood run cold. If it started raining again, that ditch could flood, submerging us in brown, muddy water. I couldn’t seem to turn my head to see anything out of the window. But out of the corner of my eye, I saw moonlight glinting on a large puddle of water very close to the car.

I tried not to panic, but when Dayne said he was going for help, I begged him, “Please don’t leave me here by myself! I don’t want to die!” “Fletch, we gotta get you out of there!” he said. “I promise you, I’m going to make it back.” Then he was gone. I couldn’t help crying. It was terrifying being down there alone like that, hidden from the road above, as evening darkened around me and the sound of cars going by became less frequent. I wanted to scream for help but for some reason, I didn’t have power in my lungs or throat. It seemed like an eternity being trapped there, unable to move. I thought about my parents and wondered if this was how my life was going to end, stuck in a car at the bottom of a ditch here in Jackson, Tennessee.

Other thoughts raced in my head as if my brain was spinning out of control. ‘How am I going to get out of here? We’ve got practice in the morning. Am I going to be able to play football tomorrow? What’s wrong with my legs?’ The tears rolled down my face. I calmed myself saying, “C’mon, man. You’ve been working out all this time—you should be able to muscle your way out of this car. Come on, Fletcher. One, two, three …” Nothing. I figured my legs must be broken, but how could that be if I didn’t feel any pain? How could I reach my parents? How badly was I hurt? I thought about my family, then about my friends from high school and my teammates. At last, I heard the sirens of the ambulance, then the voices of the ambulance driver and the paramedics at the edge of the ditch. Someone yelled, “Is anybody down there?” I thought I was yelling back, “Down here!” but I couldn’t raise my voice at all.

Someone else said, “Hey, I see somebody down there. Are you alive?” I wanted to say, “No, I’m speaking from beyond the grave.” And I thought, ‘Are you alive? What kind of question is that?!’ The floodlights from the ambulance were so bright in that dark ditch that I had to squint as I heard people racing toward me. They used the Jaws of Life, a hydraulic tool that pries metal apart to open cars in emergencies, to get me out.

Because I was lying on my right side, they had to pull me out of the car by my left arm. That was the first time I felt pain in my arm and my neck, and I yelled, “Please stop! Please stop! Something’s wrong.” They hoisted me up the steep climb in a gurney with some type of crane. In the back of the ambulance, a young woman examined me. I felt her touching my neck. Then I could hear her going through my pockets, but I couldn’t feel a thing. I was thinking, ‘Wow, that’s weird.’

She asked so many questions. “Where are you? Do you know what happened? What’s your name? Can you move your arm?” “Yes, I was in a car crash. My name is Fletcher Cleaves. I’m 18 years old,” I said, trying to steady my voice. I moved my right arm for her. “Can you move your other arm?” I moved my left arm. She said, “I want you to move your right leg.” I moved my right leg. Then she paused. She said, “Please move your right leg.” And I said, “I did!” She paused again. “Okay,” she said. “Move your left leg.” I moved my left leg. Another pause. Then she said it again. “Can you move your left leg?” “I did,” I said, feeling confused. She didn’t meet my eye, but I saw her look of concern. “Okay,” she said, “we’re going to take you to the emergency room for some tests.” That’s when I knew that something was very wrong.

She talked with someone in a low voice, and then she said, “We think you might have broken your neck.” Immediately, I asked to call my parents. Little did I know that the hospital staff had already called them, but because I was older than 18, they could only inform my parents that I was in a car crash and that they should come to the hospital right away. HIPAA privacy laws restricted the staff from providing any more details. By the time I called them, my parents were frantically driving to Jackson from Memphis. My dad was so relieved to hear me sounding coherent that he didn’t seem concerned at all when I told him I broke my neck. At that time, none of us knew exactly what that might mean in terms of recovery and long-term disability.

In the kung fu movies I watched, a guy would break his neck and immediately fall dead and that was that. So, the fact that I had a broken neck, and I was still talking didn’t make sense to me. Even though my dad was just as confused, he told me, “Fletcher, when we got the call from the hospital that you had been in a crash, we didn’t know what to think. But then when you called us and I heard you making sense and sounding like yourself, I knew that whatever else might be wrong, we can deal with it. We are on our way to you right now.” A cold feeling of dread started in my shoulders and settled on me all the way to the hospital.

At the hospital, I learned the truth. The roof of the car had caved in and broken my neck in two places. That was what had knocked me unconscious. So many people in white coats and scrubs were rushing around me, checking my vital signs, taking blood, and asking questions. My neck was locked in a brace to keep me from moving it, so all I could do was look up at the glare of the ceiling lights and try to stop shaking. I couldn’t wait for my parents to arrive. I just wanted to see a familiar face. I didn’t get to see Dayne at the hospital right away, as another team was busy working on him.

A doctor in the ER asked me, “Are you sure you and Dayne were in the same car?” He had an incredulous look on his face. “He’s all banged up, and you don’t have a scratch on you.” He told me that Dayne had been ejected from the car and must have been thrown against a tree or some bushes. His arm had been so badly injured, and he was in such a state of shock, no one could figure out how he managed to climb up a steep eight-foot embankment to get help. Dayne said later that he felt like an angel was pushing him saying, “You have to make it, you have to make it.” A young off-duty police officer had found Dayne stumbling in a church parking lot, covered with blood and disoriented, clutching his arm.

The officer called 911, and Dayne tried to tell her, “You have to find my friend. The car crashed. He’s trapped down there in the ditch.” She couldn’t make sense of what he had said because his speech was so slurred, and then he passed out. But the paramedics spotted the car and rushed down to search for me. I wished I could talk with him about it, but there was too much going on for both of us at that point. When my parents arrived, they comforted me and kept telling me I was going to be okay. They told me that some of my coaches and other players from the team had already arrived and were waiting for news about Dayne and me.

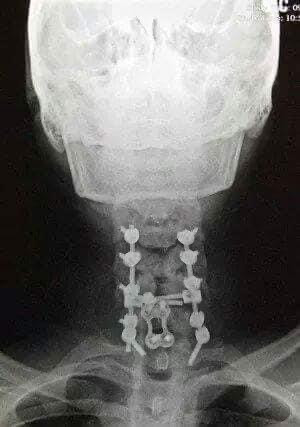

The nurse announced that they had to cut my clothes off so that they wouldn’t have to move my legs or my neck. I protested, “Hey, wait, those are my favorite shorts.” Right after that, one of the doctors explained, “We want to try a procedure first to see if we can realign your neck.” It was called a halo, and they had high hopes that it might prevent surgery and be a solution for healing the breaks in my vertebrae. I remember the doctor telling my parents, “You might want to look away for this part.” I wanted to know what they were going to do, and they said they had to drill some screws into my head for the halo. Obviously, I was horrified. I got ready for a nightmare of pain when I heard the loud buzz of the drill next to my ear, but it wasn’t that bad because I was on so many pain medications.

After the halo was around my head, they attached it to some weights to try to realign my neck. They kept asking me to relax my neck. I told them over and over that I was doing all I could, that I did feel as relaxed as possible. But my neck was so muscular from all the months of hard training for football that they couldn’t get the bones to line up again despite several tries. They took me in for surgery, but I barely remember that. In fact, when I came around afterward, they told me I had been in surgery for nine hours, and I was amazed.

Reality struck when the doctors came in and told us I was paralyzed from the breastplate down. The first thought I had was, ‘I’m not going to practice tomorrow, obviously.’ The doctors’ voices faded away as they talked with my parents. I was too busy thinking about this new reality and what I was going to do about it to listen to any more details about what I couldn’t do. It was too hard to focus on the faces of all the people in the room since my head and neck were in a brace. I could only stare up at the harsh bright ceiling lights. I felt like a piece of furniture with everyone talking about me as if I wasn’t there.

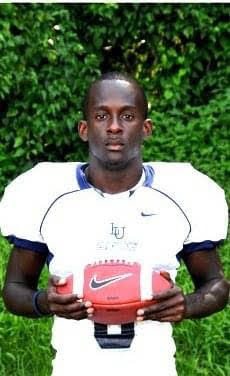

My dad had his hand on my shoulder, and I could tell he was fighting back tears. But he leaned over so that I could see his face. “Remember I told you that everything was going to be all right? Even though your body is hurt, you still have your mind and your personality.” Being 18, I didn’t have a lot of responsibilities yet, and my life was all about school, family, football, and girls. I had played football my entire life, and I understood how serious this was, but all I could think about was that I couldn’t play football anymore. Football had been my life since I was 7 years old. What was I going to do?

The first day after that talk was the lowest for me, as it began to sink in that I was really paralyzed. The doctors didn’t hold out much hope that it would ever improve. But once they told me I wasn’t going to die, I decided not to cry about it and to be a man instead—accept it and push through it. They told me what I couldn’t do, but I wanted to find out what I could do. So, I rallied right away. I had that brief taste of defeat, but I credit my support system, my family and friends, with helping me focus on hope. My football coach used to say, “The man who says he can and the man who says he can’t are both right. Which man are you going to be?”

I was going to lose momentum toward my goals—that was very evident. I was going to miss at least my entire freshman year, orientation, football season, and spring break at Daytona Beach with my friends. I was going to miss out on the life I had planned. I knew I had to really train my body and get better so that I could get out of this hospital and back to my friends and family, to the people I love. We had a family talk about the long list of all the things I wouldn’t be able to do. I watched my mother’s expression change from fear and confusion to the look of strength and determination that I knew well. It matched my own feelings and my dad’s, so we all agreed that we wouldn’t let the list stop us. People had been telling me that I couldn’t do things all my life, and I had proved them wrong. We had no intention of giving up.

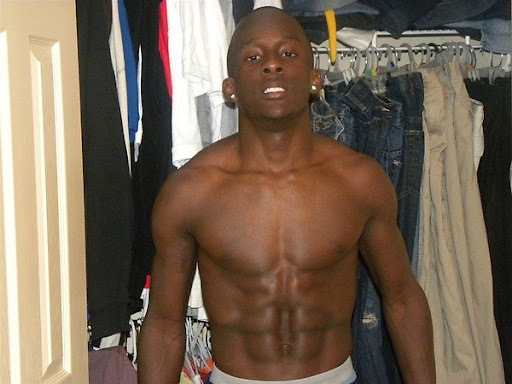

After the first surgery, the surgeon came in to talk with us. He said, “On the operating table, I tried to think of everything I could do to fix you without surgery. I felt like I was looking at a machine when I looked at your physique. You were in such great shape, your muscles were so defined—I hated to cut you open.” After a day or two of rest, the doctors realized that a second surgery would have to be done to make my neck more stable. “I’m sorry,” the lead doctor told us. “We will have to take you in for another surgery.” The look of disappointment on my parents’ faces nearly broke my heart. Seeing my mother cry out of anger and frustration was tough, but I just wanted to get fixed up and start working on getting back to my life.

My parents prayed with me, and we all asked for a miracle. I went into the second surgery feeling pretty nervous because I was more coherent this time. They told me they were going to be working near my vocal cords, and I didn’t realize they told my parents I wouldn’t be able to speak for a day or two. But against all odds, as soon as I woke up from that surgery, I opened my mouth and said quite clearly, “Where’s my dad?” My parents were shocked and said, “They told us you couldn’t speak!” I said, “Well, I’m hungry. Could I have a McGriddle?” I was healing quickly from the incisions. After a few more days, the doctors felt there was no reason to keep me in the hospital because I wasn’t sick. It was time for me to transfer to a rehabilitation facility.

Prior to the crash, I had been training hard for five months straight for college ball, and all through high school before that. My eye was always on the prize of a professional career in football. How strange it was to discover that I wasn’t getting my body in shape for football at all but for all the challenges of physical therapy ahead.

It was definitely hard to mentally cope in the beginning. I had been playing sports my entire life, and I had it taken away from me at the tender age of 18. But I chose to overcome and live a prosperous future. I did not want my accident to be the final say so of my life! I knew I was destined for greatness and I knew I wanted more out of life than just sitting at home collecting a disability check.

When I started telling my story to local football teams and high schools, people were inspired and continuously asked me to come share with other groups. I fell in love with motivating people and bringing them inspiration. I also loved the fact I was helping save lives by talking about distracted driving. My motivational speaking has covered a variety of topics including overcoming adversity, focusing on your goals and making the right choices, safe driving, the importance of education, the power of faith and forgiveness, and moving forward.

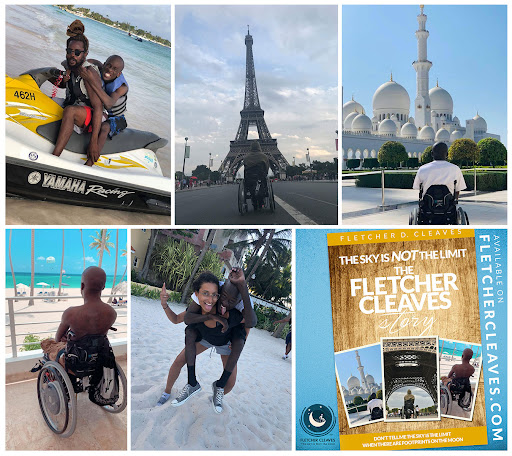

Now, 12 years after the accident, I am a world traveler, motivational speaker, college graduate, homeowner, and a Memphian who refuses to give up… and they thought the wheelchair would stop me! People think I can’t do a lot of things because of my disability, but whatever stereotype you have about me or box you want to put me in, just forget about it because I won’t fit. The sky is NOT the limit, and life is what you make it!”

You can follow his journey on: Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Website