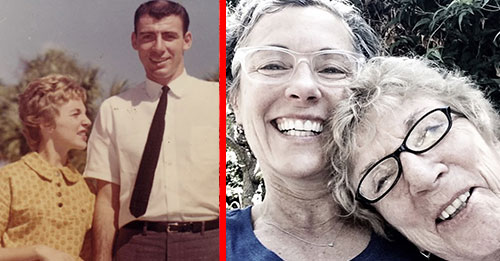

Natalie Serber was not sure if their love was unrequited, yet she clearly loved him more. Her parents met at Florida State University. Pete, an older football player, was tall, dark, and Italian. She was blond, teased, and had a nineteen-inch waist that she kept under control with Parliament cigarettes and diet pills.

Pete and Penny. She is not familiar with their courtship. She does know that they took a vacation in the summer of 1961. Penny, devastated, travelled to Provincetown, Massachusetts, and cocktailed at a homosexual nightclub. The males showed her affection. Penny preened as others played flirting and uncle-ing. She appears in images wearing black pedal pushers, a sharp bolero jacket with a vivid ribbon, and a wide grin. “Hot pink,” she once said.

Her jeans were too small by August. The males started calling her “Little Mama,” which she mistook for another nickname. Natalie was not sure what her mom thought of the missing periods, but she claims she was always irregular, as Natalie would become. Maybe she thought it was her grief, her longing for Pete. She was four months pregnant when she found she was pregnant.

Pete was keen about not having kids. Penny was certain about her desire for Pete. According to her, they pursued an abortion and inquired around, but it was too late, too difficult, and too terrifying. They notified their families, were married at the courthouse, and agreed that when the baby arrived, Penny would place it for adoption and they’d give the marriage their best. Natalie was not sure Penny considered the scenario all the way through until she left the hospital without a baby. Maybe she felt she might persuade Pete to rethink his mind.

They resided in Alphabet City, a New York City neighbourhood, in a sixth-floor walk-up with a bathtub in the kitchen. Pete tried his hand at acting. Penny awaited the arrival of the baby so that her life could start. Labor pains arrived a month early, and Penny couldn’t decide whether to choose Pete or parenthood. She gave birth at St. Vincent’s Hospital’s charity unit. Nobody who adored her held her hand in the delivery room, as was customary in the 1960s. She said she was tortured and declined to lie on her back or put her feet in the stirrups. The doctor prescribed twilight sleep. She refused to visit the infant daughter for three days. Her ward’s other moms and newborns cooed and hugged. Her mum finally saw her. Pete accompanied her to the hospital with her baggage. She relocated them to live with her aunt and uncle.

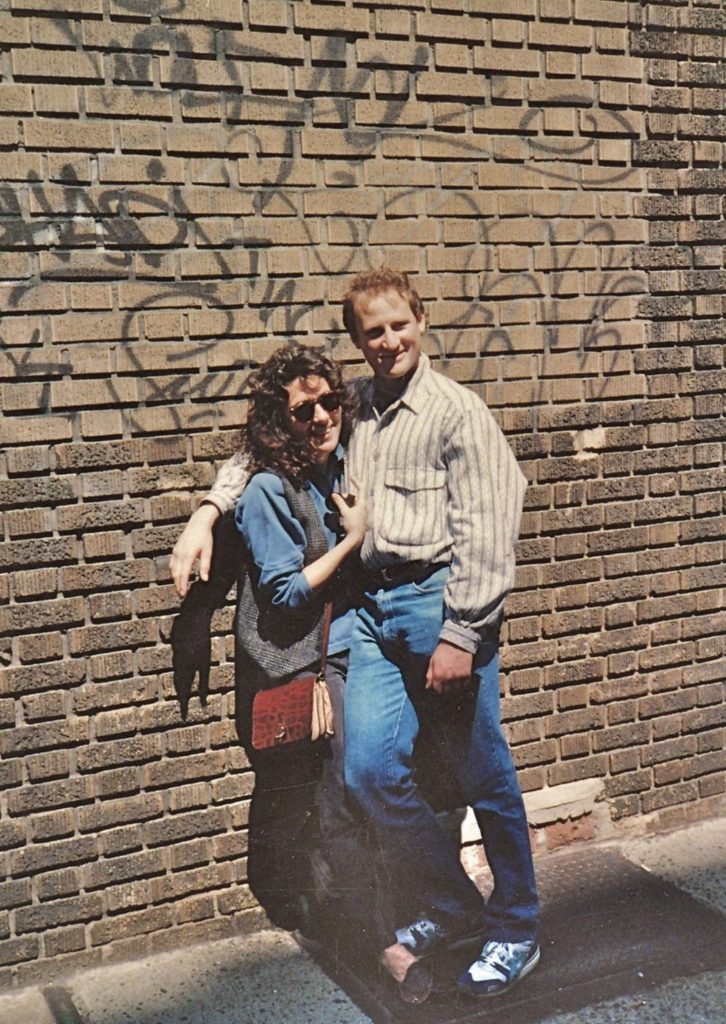

Being a single mother in 1962 was difficult. Her mom, who was 22 when she was born and believed her most significant aspect was to get her a father, underwent a string of heartbreaks at the hands of men who did not desire an “immediate family.” She was preoccupied with expenses and kid care, as well as loneliness and sadness. In her moments of sorrow, she overshared and relied too much on her. Her life would have been simpler and better if abortion had been widely available. She frequently tells her that keeping her was the finest decision she ever made, and Natalie is grateful to be alive. But it wasn’t really her choice. If abortion had been accessible, she would not have been alone and terrified on the charity ward, facing a life-changing choice.

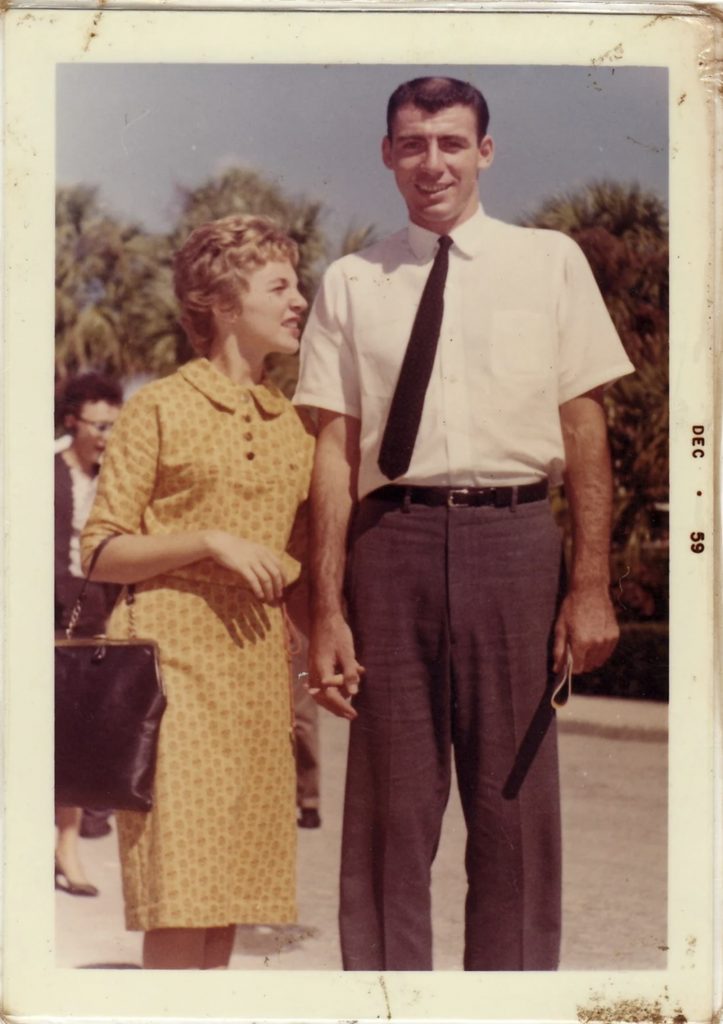

At the age of 25, Natalie fell deeply in love. Joel was boyish, witty, and kind, and they became fast friends. Their rom-com montage would include footage of them doing the sidestroke in a glistening pool, staring into one another’s eyes, and pretending to argue over the benefits of mincing or using a garlic press (mincing, of course). They sat on the same side of a restaurant banquette and had a lot of sex.

Her doctor advised her to use birth control tablets. They probably dropped secondary protection too quickly; she had a few months of breakthrough bleeding, which her doctor said was typical. But it went on for too long, and like her mom, Natalie found she was pregnant at the end of the summer. Her doctor couldn’t be sure that the high amount of hormones from the birth control that had been in her bloodstream for months was safe for a pregnancy in 1988. Joel made it quite apparent that, while he loved her, he was not prepared to be a dad. These two perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Pregnancies are terminated by individuals who love each other.

The choice tortured her. She wanted to be a mother more than anything, but she didn’t want to go through what her mother had gone through. She didn’t want to be alone. She didn’t want her child to be her confidante, roommate, or emotional support person. She just wanted her child to be a kid. She wasn’t sure if she could accomplish it on her own. She wasn’t sure whether she could be the mother she wanted to be.

She rested on Joel’s shoulder in the waiting area on the day of the abortion. He fastened her hospital gown. She shivered on the table, tears welling up in her eyes. When she informed Joel she was freezing, he went down to remove his socks and place them on her feet. Nonetheless, she had never felt so alone. It was she who had to go through the operation, not her professional and caring doctor, not her spouse who had to push his bare feet back into his oxfords. She sensed pressure, maybe scratching. There was commotion. It was sunny. That’s all she can recall.

Natalie doubt Joel and she would be together if abortion had not been accessible to her. The stress of raising a kid, the unpredictability of their careers, and the personal and marital growth they still needed to undergo would have stopped them from prospering.

Her narrative isn’t revolutionary. Her abortion had no effect on her life. Her pregnancy was not the product of any kind of violence. She’ll never know if the birth control tablets harmed a healthy child’s growth or delivery. She still adores Joel, who is now her husband, and they still dispute about the garlic press 35 years later. She cherishes her life and her two grown kids. She is glad she had an option. Her abortion provided her with the ability to be the mom she desired to be. She is sad her mum didn’t have that option.